What's the State of HIV Cure Research as 2022 Comes to an End? - The Body

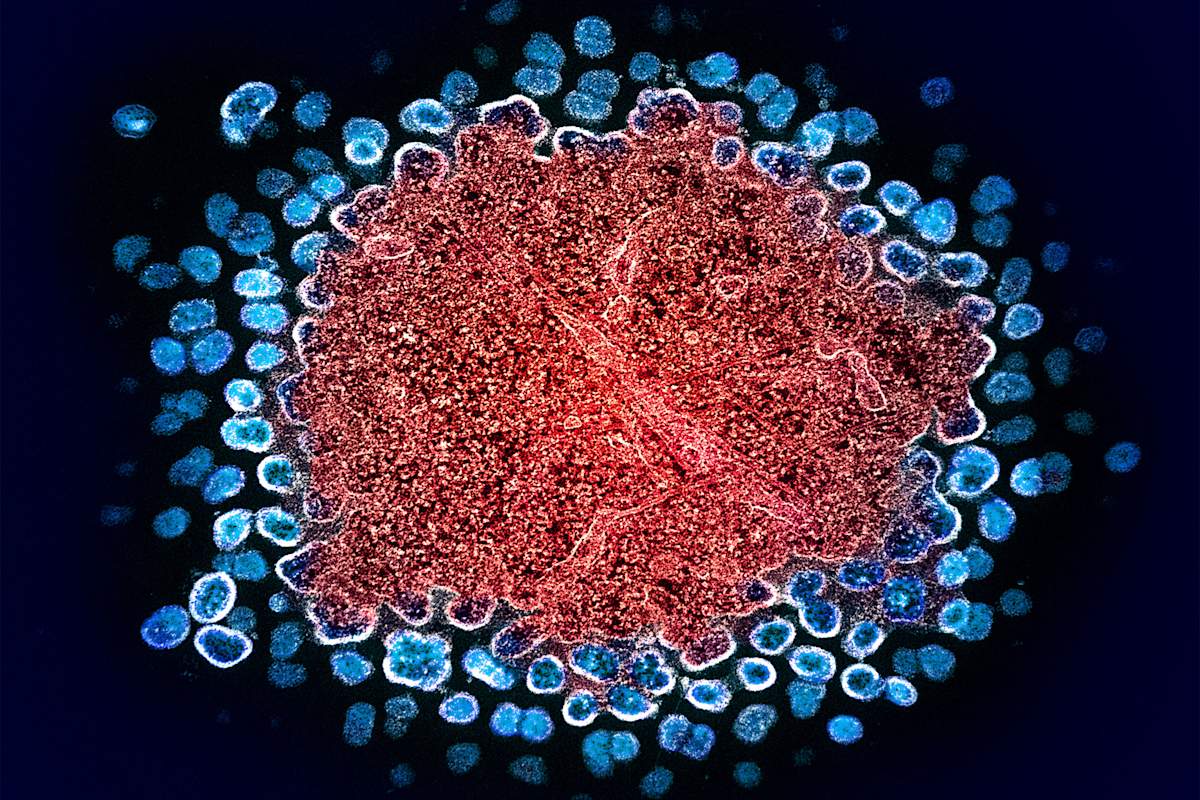

It seems as though a day did not go by in 2022 when we didn't see a headline suggesting that A BIG HIV CURE BREAKTHROUGH was right around the corner. So many early trials seem to be in play. And of course, we learned about the "New York patient," the third known person to be cured of HIV via stem-cell transplantation in the course of treatment for cancer.

But, as you might imagine, it's never as simple as newspaper headlines make it out to be. Now, that's not to say that nothing hopeful has happened—but the picture is still complicated. To help explain where things stand in cure research and why these trials are so important, TheBody spoke with Richard Jefferys―the basic science, vaccines, and Cure Project director of Treatment Action Group.

Tim Murphy: Hi, Richard! Thank you as ever for chatting with us. So, blunt question to start: What's the state of cure research? As vibrant as headlines often suggest?

Richard Jefferys: There's some encouraging evidence of progress but still no real clear path toward a universally applicable cure. There's been progress toward interventions that may benefit the immune response to HIV, but it's still frustratingly early days, with a lot of early-stage laboratory research going on.

Murphy: What is the wall that researchers are hitting?

Jefferys: There's a couple tough aspects of HIV, the biggest being that it's a virus that targets and undermines immune response, the very thing that's supposed to keep it in check. Most curative interventions reduce the amount of pathogen in the body, but they still rely on the immune system to mop up and control whatever the drugs can't get. You can't do this with HIV.

Research is trying to stack the deck in favor of the immune system as much as possible, reducing as much HIV in the body as possible. But it's still uncertain whether doing that can lead to a cure in most people.

Murphy: To ask what might seem like a stupid question, why can't they do in all people with HIV what they did in the cancer patients?

Jefferys: Those cures were achieved by completely replacing someone's immune systems with one from a donor resistant to HIV, which is effective but very dangerous and only appropriate for those with serious cancers. A stem-cell transplant comes with a 20% risk of death. You just can't translate it to other people with HIV.

Murphy: Have any other ways of eradicating HIV from the body been proven?

Jefferys: No. We've started to see evidence that what are called broadly neutralizing antibodies, or bNAbs, can help enact the immune response to HIV in a way that might trim the size of the HIV reservoir [reserve of viable HIV in the body]. There was a Rockefeller University study where giving a combination of two bNAbs correlated with reduction of HIV in the body—but it was only borderline statistically significant. And there was a second study from Denmark also involving a bNAb that seemed to increase the pace of clearance of HIV-infected cells. But unfortunately, only one person has managed to go a few years like this. Still, that provides anecdotal evidence that you might be able to get control of HIV in the body.

Right now there's a bit of a trend toward combining bNAbs with therapeutic vaccines or other immune modulators. What we want is a study where maybe up to half of people extended post-treatment natural control of HIV, but we haven't seen that yet.

Murphy: But what about these near-daily headlines promising imminent breakthroughs?

Jefferys: Obviously, different research groups are eager to promote any encouraging results they obtain, but a lot of the work tends to be pre-clinical, done in the laboratory or in animal models rather than humans. There's a lot of work involved in figuring out whether something that looked good in those cases can actually work in people.

Murphy: What is the current scope of research in actual people?

Jefferys: Most of those studies are early-phase, looking at safety or very preliminarily looking for efficacy. We're definitely starting to see larger human studies of the bNAbs—the RIO study, and a similar one in France. I think they'll have more results to share over the next year or two.

Murphy: Do you think they'll work?

Jefferys: I'm not sure. I think more likely they'll help provide guidance on how to best use these interventions, such as when to give the bNAbs.

Murphy: Then there are these rare people in the world like Loreen Willenberg and the "Esperanza patient", who seem to be able to control HIV without ever having gone on meds, or having taken them only briefly. Have we advanced in understanding why?

Jefferys: There's evidence that their immune system CD8 cells are more functional than the average person's with HIV, but there's no clear magical answer as to why. There are a lot of genetic influences on the immune system, so it can be hard to attribute it to a single factor.

Murphy: We've also gone decades without a viable HIV vaccine as well as without a cure—is there a commonality here?

Jefferys: Definitely. Both rely on encouraging the immune system to protect against HIV, either by rebuffing the virus in a preventive context or controlling it in the post-infection cure context. But the fact that HIV targets CD4 [immune] cells themselves is a big part of why it's difficult to get either a vaccine or a cure. Most vaccines prime the immune system to do its job and the virus has no direct way of interfering with that, whereas that's exactly what HIV does—interferes with and undermines the immune system.

Murphy: What would you say to people who ask, "Well, HIV treatment is pretty great these days and it's edging ever closer to 100% coverage globally, so why do we need a cure?"

Jefferys: There's the persistent stigma that people with HIV have to deal with. There's the reminder of having a chronic illness when you have to take daily treatment. And then there's the cost of lifelong treatment. PEPFAR [the U.S. program that provides HIV meds to much of the world] is a great program, but those who are dependent on it always have a background concern that if the U.S. got taken over by some crazy real estate guy, it might not want to fund PEPFAR anymore.

Murphy: Ha, that was one of the few bad things that did not happen under the crazy real estate guy. Still, you'd need as much of a huge and complex global rollout for a cure as you would for treatment, yes?

Jefferys: Yes, but ultimately it would be more cost-effective than chronic treatment. There are organizations around the world like the International AIDS Society, Caring Cross, the National Institutes of Health, and the Gates Foundation that are focused on how to prepare a global rollout of gene therapies for things like HIV and sickle-cell disease.

Murphy: So reiterate for us what you're looking forward to in 2023.

Jefferys: I think we'll start to see some of the results of gene therapy trials that could be important. A company called Excision BioTherapeutics, in collaboration with Temple University in Philadelphia, did its first human dose in July of an intervention using a CRISPR gene-editing tool, which surgically removes the HIV genetic code from remaining infected cells in the body. It sounds great, but there are concerns about whether the wrong genes might get edited, because we don't have a way of targeting those editing tools to just infected cells. Right now, they're just sending the tool into the body and hoping it ends up in the right cells.

The other potentially interesting gene therapy trial is by American Gene Technologies in Baltimore. They're trying to do gene modification of HIV-specific CD4 cells—extract them, modify them to be HIV-resistant, and put them back into bodies. Based on research they just published, some have responded well so far, but it's very variable. Now they're enrolling people in a follow-up study with a structured treatment interruption. Results should be available next year.

Murphy: That's a great summary, Richard, thanks. One more thing: For the average person living with HIV reading this who wants to see if there's an HIV cure study that's right for them, sadly there isn't a more user-friendly source than the [federal] government's clinical trials site, is there? You have to search both "HIV" and "cure." The other thing one could do is express interest to their HIV provider and see if they can connect them to something in the area.

Jefferys: There's also this chart I made [listing current cure trials], which I'll update next year if there are enough changes. And readers might also be interested in our effort to monitor the demographics of participation in HIV cure-related research.

Comments

Post a Comment